Deforestation-Free Supply Chains: Can Asian Countries Achieve Deforestation‑Free Pulp & Paper?

By: Nooraishah Omar, Editor, paperASIA

The global shift toward deforestation-free supply chains is reshaping the pulp and paper industry. Deforestation-free commitments have rapidly evolved from niche sustainability pledges into mainstream business expectations. Major buyers, from packaging companies to global FMCG brands, now integrate no-deforestation clauses into their procurement policies, while, financial institutions apply ESG screening to reforested investments, and regulators in the EU, UK and other regions are moving toward laws restricting products linked to forest loss. As demand for packaging, tissue and fibre products continues to rise and Asia, particularly Indonesia, Malaysia, China and parts of South Asia, is now a critical player in global pulp production and export. Yet this growth has often come at the expense of natural forests, peatlands and local communities. The key question is: can Asian countries, especially Indonesia, realistically achieve deforestation‑free pulp and paper?

In recent years, several of the region’s largest pulp and paper companies—like Asia Pulp & Paper (APP, part of Sinar Mas) and APRIL under Royal Golden Eagle (RGE)—have adopted zero-deforestation policies and committed to using the High Carbon Stock (HCS) Approach to preserve natural forests. According to a supply-chain mapping initiative by Trase (in partnership with the Stockholm Environment Institute), the Indonesian pulp sector achieved an 85% reduction in deforestation between around 2011 and 2019.

Trase’s mapping is particularly powerful because of its transparency: it links exported pulp to specific plantations, allowing observers to trace environmental impacts back to the ground. This progress generated real optimism among stakeholders, suggesting that deforestation-free models in pulp production can work—if executed with rigor.

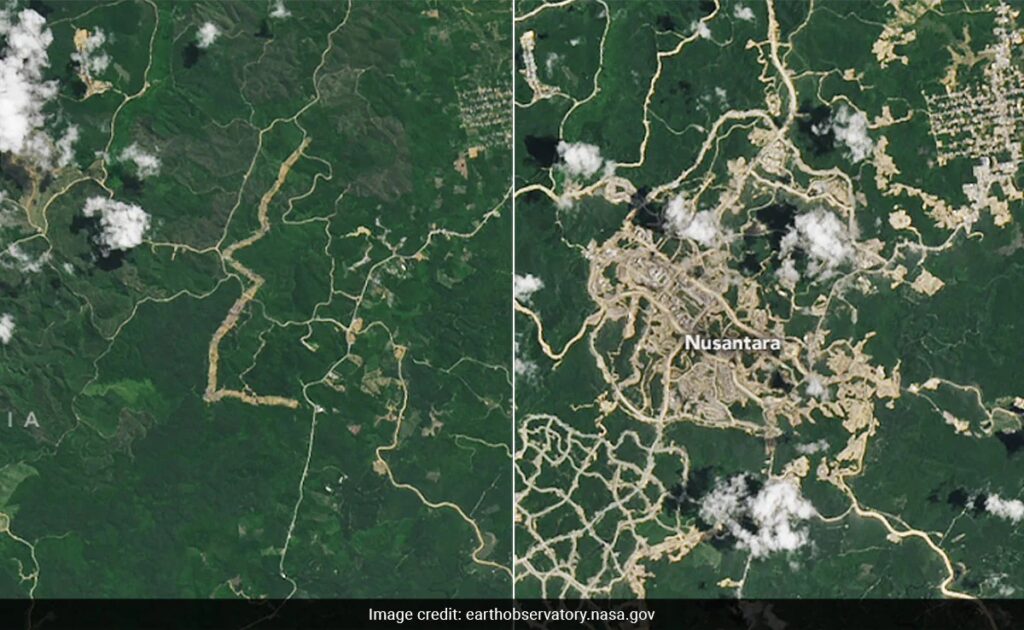

Unfortunately, recent trends show a worrying reversal. According to more recent Trase data, pulp-driven deforestation in Indonesia surged again between 2017 and 2022, increasing nearly fivefold. (Environmental Paper Network, January 2024). Much of this renewed forest loss is concentrated in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), where Trase reports that in 2022 alone, some 23,000 hectares were cleared in concessions linked to the pulp industry. The resurgence suggests that earlier reductions, while real, were fragile—and may not hold without sustained oversight and stronger structural change.

One of the major concerns for pulp and paper supply chain is the continued reliance on peatland plantations, which have large climate and fire risks. Trase’s analysis shows that pulpwood plantations are heavily located on drained peatlands, which contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and fire vulnerability.

Greenpeace has further documented APP’s failure to fully honour its peatland restoration commitments. Between 2018 and 2020, satellite imagery showed over 3,500 hectares of peatland in APP-associated concessions being cleared—even though APP has publicly pledged to protect these ecosystems. (Greenpeace, July 2020). This continuing peatland pressure not only undermines carbon goals, but also raises serious questions about the long-term sustainability of “deforestation-free” claims.

Voluntary commitments—while necessary—are not always enforced. Trase data reveal that even with zero-deforestation commitments, 170,000 hectares were deforested in pulpwood concessions during 2015–2019. Greenpeace’s 10-year review of APP’s Forest Conservation Policy also finds that the company is still linked to tens of thousands of hectares of deforestation in its supplier network. (Greenpeace, October 2023). These findings point to the need for stronger auditing, third-party verification and supply chain accountability—not just on paper.

Part of the pressure comes from expanding demand: new pulp mills are being built, and production is expanding rapidly. According to Mongabay reporting, Indonesia’s pulp production has increased substantially, fueling a renewed need for plantation land. As production scales up, the risk grows as companies will source fibre from non‑compliant suppliers or even expand into forested areas not yet under industrial concession, making deforestation-free goals harder to sustain.

Many pulpwood plantations overlap with community lands and indigenous territories, creating potential conflict. Without secure land tenure and inclusive processes, deforestation-free ambitions can clash with local rights, undermining both social justice and environmental goals.

So, is a deforestation-free pulp and paper sector in Asia realistic? Yes, but only under certain conditions, that are not yet fully met. A 5-10 years outlook will show large pulp companies with strong zero-deforestation policies continuing to reduce deforestation in their directly managed concessions and transparency tools (such as Trase) helping buyers and civil society expose non-compliance. However, recent years’ resurgence of forest loss suggests that the gains are fragile.

Achieving a truly deforestation-free pulp industry in Asia will require deep, systemic change. Governments must adopt stronger regulations, including enforceable no-deforestation policies and protections for peatland ecosystems. Full supply-chain traceability is essential, extending to all fibre suppliers across multi-tier networks. Progress also depends on restoring degraded peatlands and gradually reducing reliance on peat-based plantations. Meanwhile, financial incentives can accelerate this shift when green investments and ESG-aligned capital favour producers that meet high sustainability standards. Equally important is the engagement of local and Indigenous communities, who must have secure land rights and share fairly in the benefits of sustainable plantation management. If these conditions come together, the pulp industry could evolve into a model of sustainable production that supports both ecological integrity and human well-being.

To make this transformation possible, stakeholders will need to advance coordinated strategies. Companies should strengthen and enforce zero-deforestation commitments, apply High Carbon Stock (HCS) assessments and ensure that all suppliers comply with these standards. Governments play a central role by legislating and enforcing robust land-use protections, particularly for peatlands, and by supporting frameworks that guarantee secure land tenure. Buyers and brands can drive demand for responsibly sourced fibre by requiring deforestation-free materials and entering long-term contracts tied to sustainability performance. Financial institutions should prioritise capital for sustainable producers and impose penalties on high-risk, deforestation-linked operations. Civil society organisations and NGOs must continue independent monitoring, promote transparency and hold industry actors accountable. Above all, communities and Indigenous peoples must be treated as true partners, co-managing land, sharing benefits and having their rights fully respected.

Asia stands at a pivotal moment. The region has demonstrated that reducing deforestation in the pulp and paper sector is possible—significant reductions in forest loss during the past decade prove that. But recent rebounds in deforestation reveal that progress is fragile. Achieving fully deforestation-free pulp and paper supply chains in Asia is not out of reach. The foundations exist: corporate commitments, monitoring technologies, growing consumer pressure and increasing awareness of climate and biodiversity risks.

Yet success will depend on the ability of governments, companies, investors and communities to work together, strengthen compliance and make long-term decisions that prioritise forest protection over short-term expansion. In the coming years, the region’s choices will determine whether Asia becomes a global model for sustainable pulp production or whether new waves of deforestation undo the progress already made. The window for action remains open, but closing fast.